This question lingers on many people’s minds — who is the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time) among all athletes? Of course, there is no real answer to this question, so the topic can be admittedly puerile. On the other hand, debates around this topic are fun, intense, and sometimes involve useful analysis, data, and performance that may apply to more real-world problems. As per my knowledge about this subject, one of the key topics was distinguishing the concepts of athleticism and skill, and understanding how they correlate. This got me thinking again, and I wanted to share some thoughts. Many of these involve the idea that athleticism and skill often blend together in ways that make them hard to tease apart.

Athleticism vs Skill

Here’s a conventional way to distinguish between athleticism and skill. Athleticism in sports refers to the combination of physical attributes and skills that enables an athlete to perform well in various sports and physical activities. It encompasses more than just fitness — including qualities like strength, speed, power, agility, balance, coordination, endurance, as well as mental toughness and the ability to adapt to different situations.

Skill, in sports, refers to an athlete’s ability to perform a specific task or movement effectively and efficiently, often with a high degree of consistency and minimal effort. It includes the ability to choose and execute the correct techniques at the right time, adapting to the demands of the situation. Skills are developed through practice and training, allowing athletes to optimise performance and achieve their objectives. A simple way to explain the difference: athleticism is like the Formula 1 car, and skill is like the driver. Or, you could say athleticism is the hardware, and skill is the software.

This distinction is innate, and casual sports fans usually agree on which athletes are gifted in one area or lacking in the other. There will always be debate around skill versus athleticism. For example, most people would agree that sports like cricket and golf demand extraordinary levels of technical skill, but only moderate levels of athleticism. Track and field is the opposite. The most popular sports tend to be those that require both qualities — such as football, basketball, hockey, or baseball.

Cricket vs Track and Field

We all know that a game like cricket requires more technical skill than track and field. But I was pondering what kind of evidence might support this claim.

Take an example of a 16-year-old athlete who has never taken part in a track and field event but has all the basic athletic qualities of a State-level athlete — speed, strength, and aerobic ability. How many years of technical training would it take to develop this person into someone who could make the team? My unbiased guess is that many athletes with the necessary desire and work ethic could succeed within a year or two. In fact, we have examples of this happening in the past — such as Willie Gault, who turned raw speed into pro-level football performance with just a few years of specific practice.

Now imagine the same hypothetical scenario with cricket. How many years of technical training would it take to turn a raw athletic talent into someone who can play at the base level? Even for the simplest positions, it would probably take more than a few years to develop the necessary batting, bowling, and fielding skills. And for a specialist batter or bowler, the timeline would be even longer. In fact, we might guess that many superior athletes could never acquire the necessary skills — even with a decade of high-quality practice. Not everyone can do this.

So one way to measure the skill requirement of a sport is to ask how many years of specific practice the average pro needs to get where they are. In sports like golf, tennis, and cricket, the best performers usually start young and specialise before their teens. In sports like football or basketball, general athletic ability takes you a long way, and you can delay specialisation until late high school or even college.

Nature vs Nurture

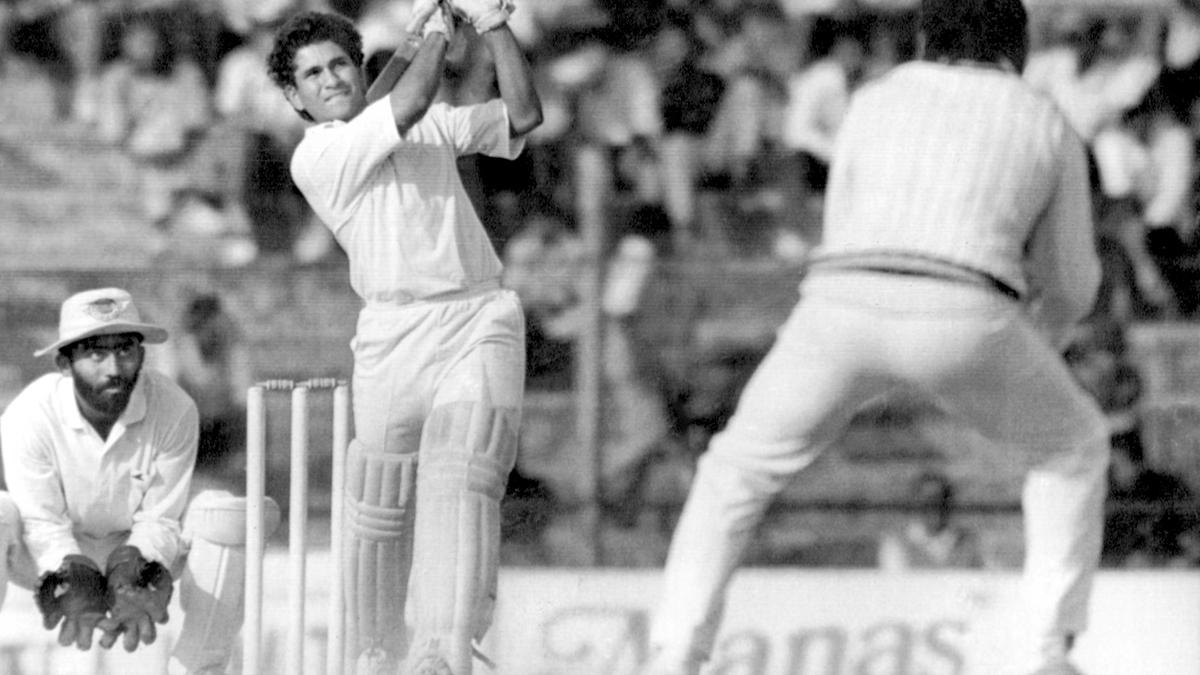

Another interesting difference between athleticism and skill is the role of natural talent versus training. Many elite athletes don’t train much aside from just playing their sport. For example, Sachin Tendulkar avoided heavy weight training in his early years, and so did M. S. Dhoni and Kapil Dev. I’ve personally heard from many athletes across sports who literally didn’t lift weights — for various reasons. It seems that for some genetically gifted people, elite athleticism is their natural state, and they need to do very little to maintain it. And for those without genetic gifts, there is no amount of training that will allow them to score a century, run a sub-5.3 in 40 metres, or a sub-19-minute 5K.

Technical skill is different. In most cases, it correlates closely with hours of practice — like the 10,000-hour rule to become elite. For example, if you watch five to six-year-old kids playing with a ball, you will notice huge differences in hand–eye coordination. This is probably caused more by differences in hours of practice than natural talent. Some kids start playing as soon as they can crawl and soon clock hundreds of hours. Others never gain that experience. So it can be hard to separate natural talent from natural interest.

Still, the existence of prodigies shows us that natural talent in physical skill acquisition is real. Some kids learn sports techniques way faster than others — even with equal training. This is especially true in cricket, golf, tennis, and gymnastics, where young kids sometimes reach technical levels that adults never achieve even after years of training. Perhaps it has something to do with how the nervous system processes and stores information related to deciphering physical snags. In other words, some people simply have higher ‘movement IQ’ than others.Also, the speed of skill acquisition may depend on athleticism. In tennis or cricket, proper stroke technique requires some baseline level of speed, power, balance, and agility. I’ve seen many cricketers decline in their technical skill over time — not because they were out of practice, but because their athleticism declined. When you watch them play, their bat work may look sloppy — but slow feet might be to blame. When your feet are slow, your hands feel dumb.

Skill vs Structure

Good technique is also affected by the body’s physiology — something often overlooked in discussions around coordination. Good skill or technique can only be acquired when the body is aligned with the right movement patterns. If the body is not moving in the right way, it takes time to adapt the movement pattern through more practice. In cricket or golf, players bowl or swing — which means delivering the ball or club along the path of least resistance, according to the natural grooves of their body. This is determined by the relative strengths and flexibility of their muscles, variations in limb length, joint angles, etc. People with different body types will naturally bowl or swing along different trajectories, and some of these are far more functional and effective than others. The more successful patterns tend to become the norm for comparison.

Another clue that physical structure plays a big role in coordination is our intuitive ability to identify good athletes based purely on appearance — even when they’re not performing. This could be called genetic physiological loading. Many times, we see someone on the street who gives the impression of being a professional athlete — and sometimes, we’re fooled by the structure. Generally speaking, it comes down to proportional build or simply the way they move.

There are plenty of big guys in the gym who don’t look like athletes. It’s more about how they carry themselves — powerful and graceful, like a jungle cat.

Skill vs Passion and Psychology

Passion and psychology also play a key role in how fast someone learns a skill. Passionate people spend enormous amounts of time focussing intensely on perfecting a skill. An example I read about: when Tiger Woods was a kid, he used to watch his dad practise his golf swing. As he grew older, he’d even ask his driver to stop the car during long trips so he could step out and practise swings on the roadside. His natural talent, passion, and psychology were all interconnected.

GOAT athletes are of a different breed — combining physical, mental, social, and skill-based strengths. They are the icons of their sport — one in a million.